Ancient Roman Theaters

Roman theatres derive their basic design from the Theatre of Pompey, the first permanent Roman theatre. The characteristics of Roman to those of the earlier Greek theatres due in large part to its influence on the Roman triumvir Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Much of the architectural influence on the Romans came from the Greeks, and theatre structural design was no different from other buildings. However, Roman theatres have specific differences, such as being built upon their own foundations instead of earthen works or a hillside and being completely enclosed on all sides.

The Roman theatre was shaped with a half circle or orchestra space in front of the stage. Most often the audience sat here in comfortable chairs. Occasionally, however, the actors would perform in this space. To solve the problem of lighting and sound - the theaters were outdoors.

The Romans built theaters anywhere, even on flat plains, by raising the whole structure off the ground. As a result, the whole structure was more integrated and entrances/exits could be built into the cave, as is done in large theaters and sports arenas today. The arena was as high as the rest of the structure, so the audience could not look out beyond the stage. It also created more of an enclosed atmosphere and may have helped keep out the noises of the city. A tarp could be rigged and moved over the top of the theater to create shade.

The huge amount of people present still held problems for the sound as the audience would not always stay quiet. To solve this problem, costumes and mask were worn to show the type of person on stage. Different symbols were worked out. The actors wore masks - brown for men, white for women, smiling or sad depending on the type of play. The costumes showed the audience who the person was - a purple gown for a rich man, a striped toga for a boy, a short cloak for a soldier, a red toga for a poor man, a short tunic for a slave etc. Women were not allowed to act, so their parts were normally played by a man or young boys wearing a white mask.

The actors spoke the lines, but a second actor mimed the gestures to fit the lines, along with background music. Some things were represented by a series of gestures, which are recognized by the audience to mean something, such as feeling a pulse to show a sick person, making the shape of a lyre with fingers to show music. The audience was often more interested in their favorite actors than the play itself. The actors would try to win over the audience's praise with decorative masks, costumes, dancing and mime.

If the play scripted an actor's dying, a condemned man would take the place of the actor at the last moment and actually be killed on stage. The Romans loved the bloodthirsty spectacles. Emperors such as Nero used the theatre as a way of showing their own talents - good or otherwise. Nero actually used to sing and would not let anyone leave until he was finished.

Most theaters still standing date from the Hellenistic period, which dates from the 4th century BC and later. It's possible to assume much of the features were preserved, but not definitely. This is due to the fact that most plays completely lacked staging directions. Those directions found in modern translations were merely added by the translator. Some plays, however, do sometimes contain scenic requirements.

Pompeii's large theatre underwent a structural change from the Hellenistic style to a more Greco-Roman style. The traditional Hellenistic theatres had the scene section moved forward into the orchestra area, reducing it to a semicircle. The front portion of the scene converted into a 'proskeniontogeion' (high raised stage). The stage was 8-12 feet, 45-140 feet in width, and 6.5-14 feet in depth. The back wall of the stage had 1-3 doors that opened onto the stage but later the number of doors increased to 1-7, depending on the theatre. The stage was supported in front by open columns.

Triangular wooden prisms with a different scene painted on each side (periaktoi) were created and located near the side entrance of the stage. This allowed for a more realistic show. The higher stage gave way to better acting which later attracted actors and popularity.

After the Romans moved into the area and built the odium, Pompeii's theatre underwent complete changes and in 65 A.D, the theatre transformed away from the Hellenistic style into the Greco-Roman style of theatre. A porticos was added in the back of the theatre. The ends of the scene building were removed.

Rows of seats were added for honored guests. The stage was lowered and 2 short flights of steps leading down to the stairs were added. These changes were important because the intent of the theatre was to replace the temporary wooden stages that the Romans were using to house their tragedies and comedies. The new look of the theatre is what was left to the world after Vesuvius's fatal eruption.

The earliest known Italian drama, is known to come from the region of Campania, which is located in the Southern half of Italy. It was in the town of Atella where the Atellan Farces became popular. These were originally written in the language of Oscan, and later translated into Latin as these farces caught on in Rome. What allowed theses plays to catch on, however, was actually due to the Etruscans from the North, as well as Greek colonies located on the Eastern side of the Peninsula to whom the Romans have given the credit of introducing the many forms of music and dance.

In 364 B.C., the Romans specifically introduced the Etruscan form of the ballet as a dance so as to appease the gods, so that they might remove a plague from the empire. Livius Andronicus, who is thought to be a freed slave during the 3rd century B.C., is credited for translating the first Greek plays into Latin as well as producing them (Butler 79). Many of the performances were associated with important holidays as well as with religious festivals.

Roman theatres were built in all areas of the empire from medieval-day Spain, to the Middle East. Because of the Romans' ability to influence local architecture, we see numerous theatres around the world with uniquely Roman attributes.

There exist similarities between the theatres and amphitheatres of ancient Rome/Italy. They were constructed out of the same material, Roman concrete, and provided a place for the public to go and see numerous events throughout the Empire. However, they are two entirely different structures, with specific layouts that lend to the different events they held. Amphitheatres did not need superior acoustics, unlike those provided by the structure of a Roman theatre. While amphitheatres would feature races and gladiatorial events, theatres hosted events such as plays, pantomimes, choral events, and orations. Their design, with its semicircular form, enhances the natural acoustics, unlike Roman amphitheatres constructed in the round.

These buildings were semi-circular and possessed certain inherent architectural structures, with minor differences depending on the region in which they were constructed. The scaenae frons was a high back wall of the stage floor, supported by columns. The proscaenium was a wall that supported the front edge of the stage with ornately decorated niches off to the sides. The Hellenistic influence is seen through the use of the proscaenium. The Roman theatre also had a podium, which sometimes supported the columns of the scaenae frons. The scaenae was originally not part of the building itself, constructed only to provide sufficient background for the actors. Eventually, it became a part of the edifice itself, made out of concrete. The theatre itself was divided into the stage (orchestra) and the seating section (auditorium). Vomitoria or entrances and exits were made available to the audience.

The auditorium, the area in which people gathered, was sometimes constructed on a small hill or slope in which stacked seating could be easily made in the tradition of the Greek Theatres. The central part of the auditorium was hollowed out of a hill or slope, while the outer radian seats required structural support and solid retaining walls. This was of course not always the case as Romans tended to build their theatres regardless of the availability of hillsides. All theatres built within the city of Rome were completely man-made without the use of earthworks. The auditorium was not roofed; rather, awnings (vela) could be pulled overhead to provide shelter from rain or sunlight.

Some Roman theatres, constructed of wood, were torn down after the festival for which they were erected concluded. This practice was due to a moratorium on permanent theatre structures that lasted until 55 BC when the Theatre of Pompey was built with the addition of a temple to avoid the law. Some Roman theatres show signs of never having been completed in the first place.

Inside Rome, few theatres have survived the centuries following their construction, providing little evidence about the specific theatres. Arausio, the theatre in modern-day Orange, France, is a good example of a classic Roman theatre, with an indented scaenae frons, reminiscent of Western Roman theatre designs, however missing the more ornamental structure. The Arausio is still standing today and, with its amazing structural acoustics and having had its seating reconstructed, can be seen to be a marvel of Roman architecture.

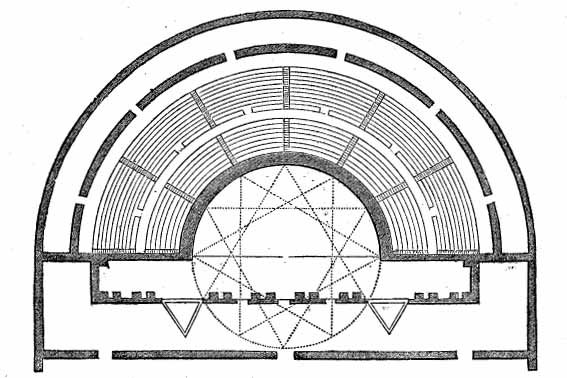

Standard Floor Plan

Standard Floor PlanTheatre Structure

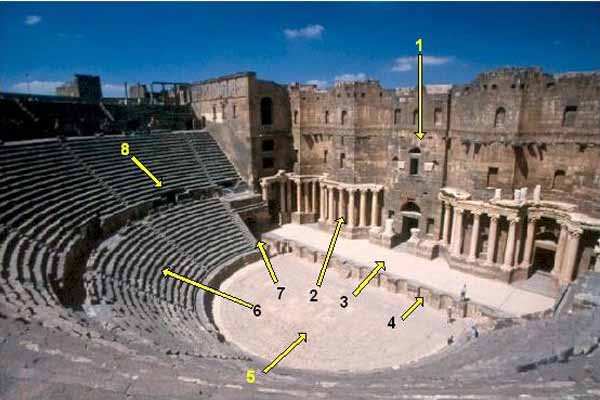

Interior view of the auditorium

1) Scaenae frons 2) Porticus post scaenam 3) Pulpitum 4) Proscaenium

5) Orchestra 6) Cavea 7) Aditus maximus 8) Vomitorium

The scaenae frons is the elaborately decorated background of a Roman theatre stage. This area usually has several entrances to the stage including a grand central entrance. The scaenae frons is two or sometime three stories in height and was central to the theatre's visual impact for this was what is seen by a Roman audience at all times. Tiers or balconies were supported by a generous number of classic columns. This style was influenced by Greek theatre. The Greek equivalent was the "Scene" building. It lends its name to "proscenium," which describes the stage or space "before the scene."

The pulpitum is a common feature in medieval cathedral and monastic architecture in Europe. It is a massive screen, most often constructed of stone, or occasionally timber, that divides the choir (the area containing the choir stalls and high altar in a cathedral, collegiate or monastic church) from the nave and ambulatory (the parts of the church to which lay worshippers may have access).

A proscenium is the area of a theater surrounding the stage opening. Note that a proscenium theatre should not be confused with a "proscenium arch theatre".

The cavea were the subterranean cells in which wild animals were confined before the combats in the Roman arena or amphitheatre.

A vomitorium is a passage situated below or behind a tier of seats in an amphitheatre, through which big crowds can exit rapidly at the end of a performance.They are also a pathway for actors to enter on and off stage. The Latin word vomitorium, plural vomitoria, derives from the verb vomeo, vomere, vomitum, "to spew forth." In ancient Roman architecture, vomitoria were designed to provide rapid egress for large crowds at amphitheatres and stadiums, as they do in modern sports stadiums and large theaters.

Theatre of Marcellus

The one ancient theatre to survive in Rome, the Theatre of Marcellus, was started by Caesar and completed by Augustus around the year 11 or 13. It stands on level ground and is supported by radiating walls and concrete vaulting. An arcade with attached half-columns runs around the building. The columns are Doric and Ionic.

At the theatre, locals and visitors alike were able to watch performances of drama and song. Today its ancient edifice in the rione of Sant'Angelo, Rome, once again provides one of the city's many popular spectacles or tourist sites. It was named after Marcus Marcellus, Emperor Augustus's nephew, who died five years before its completion. Space for the theatre was cleared by Julius Caesar, who was murdered before it could be begun; the theatre was so far advanced by 17 BC that part of the celebration of the ludi saeculares took place within the theatre; it was completed in 13 BC and formally inaugurated in 12 BC by Augustus.

The theatre was 111 m in diameter; it could originally hold 11,000 spectators. It was an impressive example of what was to become one of the most pervasive urban architectural forms of the Roman world. The theatre was built mainly of tuff, and concrete faced with stones in the pattern known as opus reticulatum, completely sheathed in white travertine. The network of arches, corridors, tunnels and ramps that gave access to the interiors of such Roman theaters were normally ornamented with a screen of engaged columns in Greek orders: Doric at the base, Ionic in the middle. It is believed that Corinthian columns were used for the upper level but this is uncertain as the theater was reconstructed in the Middle Ages, removing the top tier of seating and the columns.

Like other Roman theaters in suitable locations, it had openings through which the natural setting could be seen, in this case the Tiber Island to the southwest. The permanent setting, the scaena, also rose to the top of the cavea as in other Roman theaters.

The name templum Marcelli still clung to the ruins in 998. In the Early Middle Ages the Teatro di Marcello was used as a fortress of the Fabii and then at the end of the 11th century, by Pier Leoni and later his heirs (the Pierleoni). The Savelli held it in the 13th century. Later, in the 16th century, the residence of the Orsini, designed by Baldassare Peruzzi, was built atop the ruins of the ancient theatre.

Now the upper portion is divided into multiple apartments, and its surroundings are used as a venue for small summer concerts; the Portico d'Ottavia lies to the north west leading to the Roman Ghetto and the Tiber to the south west.

In the 17th century, the renowned English architect Sir Christopher Wren explicitly acknowledged that his design for the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford was influenced by Serlio's engraving of the Theatre of Marcellus.

Theatre at Orange

The Theatre of Orange is an ancient Roman theatre, in Orange, southern France, built early in the 1st century CE. It is owned by the municipality of Orange and is the home of the summer opera festival, the Choregies d'Orange.

It is one of the best preserved of all the Roman theatres in the Roman colony of Arausio (or, more specifically, Colonia Julia Firma Secundanorum Arausio: "the Julian colony of Arausio established by the soldiers of the second legion") which was founded in 40 BC. Playing a major role in the life of the citizens, who spent a large part of their free time there, the theatre was seen by the Roman authorities not only as a means of spreading Roman culture to the colonies, but also as a way of distracting them from all political activities. Mime, pantomime, poetry readings and the "attelana" (a kind of farce rather like the commedia dell'arte) was the dominant form of entertainment, much of which lasted all day. For the common people, who were fond of spectacular effects, magnificent stage sets became very important, as was the use of stage machinery. The entertainment offered was open to all and free of charge.

As the Western Roman Empire declined during the 4th century, by which time Christianity had become the official religion, the theatre was closed by official edict in AD 391 since the Church opposed what it regarded as uncivilized spectacles. After that, the theatre was abandoned completely. It was sacked and pillaged by the "barbarians" and was used as a defensive post in the Middle Ages. During the 16th-century religious wars, it became a refuge for the townspeople.