Circus

The Roman circus (from Latin, "circle") was a large open-air venue used for public events in the ancient Roman Empire. The circuses were similar to the ancient Greek hippodromes, although serving varying purposes. Along with theatres and amphitheater, circuses were one of the main entertainment sites of the time. Circuses were venues for chariot races, horse races, and performances that commemorated important events of the empire were performed there. For events that involved re-enactments of naval battles, the circus was flooded with water.

The performance space of the Roman circus was normally, despite its name, an oblong rectangle of two linear sections of race track, separated by a median strip running along the length of about two thirds the track, joined at one end with a semicircular section and at the other end with an undivided section of track closed (in most cases) by a distinctive starting gate known as the carceres, thereby creating a circuit for the races. The Circus of Maxentius epitomises the design.

The median strip was called the spina and usually featured ornate columns, statues and commemorative obelisks. The turning points on either end of the spina were usually marked by conical poles, called the metae (singular: meta).

The performance surface of the circus was normally surrounded by ascending seating along the length of both straight sides and around the curved end, though there were sometimes interruptions in the seating to provide access to the circus or the seating, or to provide for special viewing platforms for dignitaries and officials. One circus, that at Antinopolis (Egypt), displays a distinct gap of some 50m between the carceres and the start of the ascending seating where there is apparently no structure. This appears to be an exception.

The great majority of circuses fit the description above. Those that do not display two different variations: that at Emerita Augusta (MŽrida, Spain), where the carceres end is substituted by a slightly curved 'straight' end joined to the straight sides of ascending seating by rounded corners of ascending seating; and a few in which the carceres end is substituted by a second semi-circular end to produce an oval shaped arena. These latter circuses are normally small (Nicopolis (Greece) and Aphrodisias (Turkey)), and should probably be considered stadiums. The exception to this are the enigmatic traces of the huge oval circus near Montaperti (Italy) which appears to be somewhat unique in that, in addition to its unusual combination of dimensions and shape, is not, apparently, close to any contemporary Roman settlement.

There are similar buildings, called stadia, which were used for Greek style athletics. These buildings were similar in design but typically smaller than circuses; however, the distinction is not always clear.

Differently from other major Roman structures circuses frequently evolved over long periods of time from a simple track in a field, through generations of wooden seating structures (frequently destroyed by fire or rot), before they finally began to be converted to stone. Although circuses such as the Circus Maximus (Italy) may have existed in some form from as early as around 500BC, circuses were mainly constructed during the 400 years between 200BC and 200AD.

Circuses do not appear to have been constructed with any special compass orientation. Those that are well identified can be found with their round ends oriented around the compass.

Circus Maximus

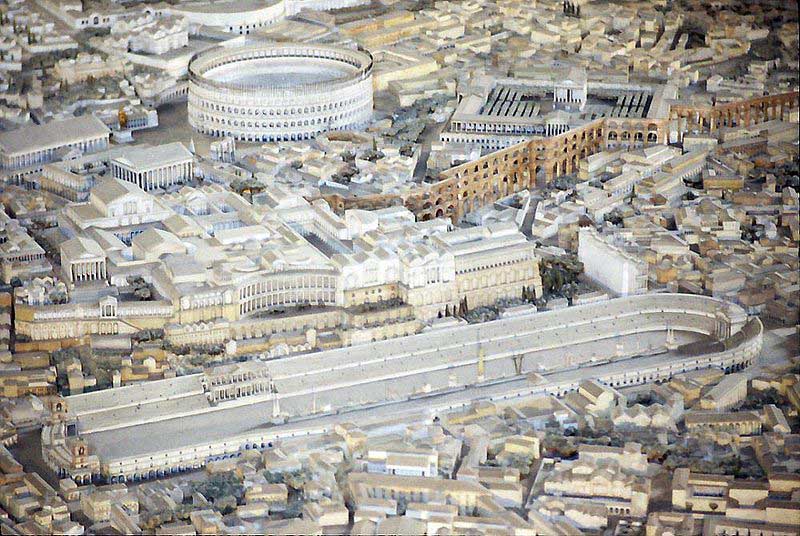

Model of ancient Rome in the Imperial era, showing the Circus Maximus (foreground),

the Colliseum (top of picture) and between them, the Palatine

Circus Maximus is an ancient Roman chariot racing stadium and mass entertainment venue located in Rome, Italy. Situated in the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, it was the first and largest stadium in ancient Rome and its later Empire. It measured 621 m (2,037 ft) in length and 118 m (387 ft) in width, and could accommodate about 150,000 spectators. In its fully developed form, it became the model for circuses throughout the Roman Empire. The site is now a public park.

The Circus was Rome's largest venue for ludi, public games connected to Roman religious festivals. Ludi were sponsored by leading Romans or the Roman state for the benefit of the Roman people (populus Romanus) and gods. Most were held annually or at annual intervals on the Roman calendar. Others might be given to fulfill a religious vow, such as the games in celebration of a triumph. The earliest known triumphal ludi at the Circus were vowed by Tarquin the Proud to Jupiter in the late Regal era for his victory over Pometia.

Ludi ranged in duration and scope from one-day or even half-day events to spectacular multi-venue celebrations held over several days, with religious ceremonies and public feasts, horse and chariot racing, athletics, plays and recitals, beast-hunts and gladiator contests. These greater ludi at the Circus began with a flamboyant parade (pompa circensis), much like the triumphal procession, which marked the purpose of the games and introduced the participants.

During the Republic, the aediles organized the games. Although their original purpose was religious, the complexity of staging ludi became a way to display the competence, generosity, and fitness for higher office of the organizer. Some Circus events, however, seem to have been relatively small and intimate affairs.

In 167 BC, "flute players, scenic artists and dancers" performed on a temporary stage, probably erected between the two central seating banks. Others were enlarged at enormous expense to fit the entire space. A venatio held there in 169 BC, one of several in the 2nd century, employed "63 leopards and 40 bears and elephants", with spectators presumably kept safe by a substantial barrier.

As Rome's provinces expanded, existing ludi were embellished and new ludi invented by politicians who competed for divine and popular support. By the late Republic, ludi were held on 57 days of the year; an unknown number of these would have required full use of the Circus.

On many other days, charioteers and jockeys would need to practice on its track. Otherwise, it would have made a convenient corral for the animals traded in the nearby cattle market, just outside the starting gate. Beneath the outer stands, next to the Circus' multiple entrances, were workshops and shops. When no games were being held, the Circus at the time of Catullus (mid-1st century BC) was likely "a dusty open space with shops and booths ... a colorful crowded disreputable area" frequented by "prostitutes, jugglers, fortune tellers and low-class performing artists.

With the end of the Republic, Rome's emperors met the ever-burgeoning popular demand for regular ludi and the need for more specialized venues, as essential obligations of their office and cult. Over the several centuries of its development, the Circus Maximus became Rome's paramount specialist venue for chariot races. By the late 1st century AD, the Colliseum had been built to host most of the city's gladiator shows and smaller beast-hunts, and most track-athletes competed at the purpose-designed Stadium of Domitian, though long-distance foot races were still held at the Circus. Eventually, 135 days of the year were devoted to ludi.

Even at the height of its development as a chariot-racing circuit, the circus remained the most suitable space in Rome for religious processions on a grand scale, and was the most popular venue for large-scale venationes; in the late 3rd century, the emperor Probus laid on a spectacular Circus show in which beasts were hunted through a veritable forest of trees, on a specially built stage. With the advent of Christianity as the official religion of the Empire, ludi gradually fell out of favor. The last known beast-hunt at the Circus Maximus took place in 523, and the last known races there were held by Totila in 549.

Regal Era

The Circus Maximus was sited on the level ground of the Valley of Murcia (Vallis Murcia), between Rome's Aventine and Palatine Hills. In Rome's early days, the valley would have been rich agricultural land, prone to flooding from the river Tiber and the stream which divided the valley. The stream was probably bridged at an early date, at the two points where the track had to cross it, and the earliest races would have been held within an agricultural landscape, "with nothing more than turning posts, banks where spectators could sit, and some shrines and sacred spots".

In Livy's history of Rome, the first Etruscan king of Rome built raised, wooden perimeter seating at the Circus for Rome's highest echelons (the equites and patricians), probably midway along the Palatine straight, with an awning against the sun and rain. His grandson, Tarquinius Superbus, added the first seating for citizen-commoners (plebs, or plebeians), either adjacent or on the opposite, Aventine side of the track. Otherwise, the Circus was probably still little more than a trackway through surrounding farmland. By this time, it may have been drained but the wooden stands and seats would have frequently rotted and been rebuilt. The turning posts (metae), each made of three conical stone pillars, may have been the earliest permanent Circus structures; an open drainage canal between the posts would have served as a dividing barrier

Republican Era

The games' sponsor (editor) usually sat beside the images of attending gods, on a conspicuous, elevated stand (pulvinaria) but seats at track perimeter offered the best, most dramatic close-ups. In 494 BC (very early in the Republican era) the dictator M. Valerius Maximus and his descendants were granted rights to a curule chair at the southeastern turn, an excellent viewpoint for the thrills and spills of chariot racing. In the 190s BC, stone track-side seating was built, exclusively for senators.

Permanent wooden starting stalls were built in 329 BC. They were gated, brightly painted, and staggered to equalize the distances from each start place to the central barrier. In theory, they might have accommodated up to 25 four-horse chariots abreast but when team-racing was introduced, they were widened, and their number reduced.

By the late Republican or early Imperial era, there were twelve stalls. Their divisions were fronted by herms that served as stops for spring-loaded gates, so that twelve light-weight, four-horse or two-horse chariots could be simultaneously released onto the track. The stalls were allocated by lottery, and the various racing teams were identified by their colors. Typically, there were seven laps per race.

From at least 174 BC, they were counted off using large sculpted eggs; Castor and Pollux, who were born from an egg, were divine patrons of horses, horsemen, and the equestrian order (equites). In 33 BC, an additional system of large bronze dolphin-shaped lap counters was added, positioned well above the central dividing barrier (euripus) for maximum visibility.

Julius Caesar's development of the Circus, commencing around 50 BC, extended the seating tiers to run almost the entire circuit of the track, barring the starting gates and a processional entrance at the semi-circular end. The track measured approximately 621 m (2,037 ft) in length and 150 m (387 ft) in breadth. A canal was cut between the track perimeter and its seating to protect spectators and help drain the track.

The inner third of the seating formed a trackside cavea. Its front sections along the central straight were reserved for senators, and those immediately behind for equites. The outer tiers, two thirds of the total, were meant for Roman plebs and non-citizens. They were timber-built, with wooden-framed service buildings, shops and entrance-ways beneath. The total number of seats is uncertain, but was probably in the order of 150,000; Pliny the Elder's estimate of 250,000 is unlikely. The wooden bleachers were damaged in a fire of 31 BC, either during or after construction.

Imperial Era

The fire damage of 31 was probably repaired by Augustus (Caesar's successor and Rome's first emperor). He modestly claimed credit only for an obelisk and pulvinar at the site but both were major projects. Ever since its quarrying, long before Rome existed, the obelisk had been sacred to Egyptian Sun-gods. Augustus brought it from Heliopolis at enormous expense, and erected midway along the dividing barrier. It was the first obelisk brought to Rome, an exotically sacred object and a permanent reminder of Augustus' victory over his Roman foes and their Egyptian allies in the recent civil wars. Thanks to him, Rome had secured both a lasting peace and a new Egyptian Province. The pulvinar was built on monumental scale, a shrine or temple (aedes) raised high above the trackside seats. Sometimes, while games were in progress, Augustus watched from there, alongside the gods. Occasionally, his family would join him there. This is the Circus described by Dionysius of Halicarnassus as "one of the most beautiful and admirable structures in Rome", with "entrances and ascents for the spectators at every shop, so that the countless thousands of people may enter and depart without inconvenience."

The site remained prone to flooding, probably through the starting gates, until Claudius made improvements there; they probably included an extramural anti-flooding embankment. Fires in the crowded, wooden perimeter workshops and bleachers were a far greater danger. A fire of 36 AD seems to have started in a basket-maker's workshop under the stands, on the Aventine side; the emperor Tiberius compensated various small businesses there for their losses.

In AD 64, during Nero's reign, fire broke out at the semi-circular end of the Circus, swept through the stands and shops, and destroyed much of the city. Games and festivals continued at the Circus, which was rebuilt over several years to the same footprint and design.

By the late 1st century AD, the central dividing barrier comprised a series of water basins, or else a single watercourse open in some places and bridged over in others. It offered opportunities for artistic embellishment and decorative swagger, and included the temples and statues of various deities, fountains, and refuges for those assistants involved in more dangerous circus activities, such as beast-hunts and the recovery of track-side casualties.

In AD 81 the Senate built a triple arch honoring Titus at the semi-circular end of the Circus, to replace or augment a former processional entrance. The emperor Domitian built a new, multi-story palace on the Palatine, connected somehow to the Circus; he likely watched the games in autocratic style, from high above and barely visible to those below. Repairs to fire damage during his reign may already have been under way before his assassination.

The risk of further fire-damage, coupled with Domitian's fate, may have prompted Trajan's decision to rebuild the Circus entirely in stone, and provide a new pulvinar in the stands where Rome's emperor could be seen and honored as part of the Roman community, alongside her gods. Under Trajan, the Circus Maximus found its definitive form, which was unchanged thereafter save for some monumental additions by later emperors, repairs and renewals to existing fabric, and an extensive, planned rebuilding of the starting gate area under Caracalla.

The southeastern turn of the track ran between two shrines which may have predated the Circus' formal development. One, located at the outer southeast perimeter, was dedicated to the valley's eponymous goddess Murcia, an obscure deity associated with a sacred spring, the stream that divided the valley, and the lesser peak of the Aventine Hill.

The other was at the southeastern turning-post; an underground shrine to Consus, a minor god of grain-stores, connected to the grain-goddess Ceres and to the underworld. According to Roman tradition, Romulus discovered this shrine shortly after the founding of Rome. He invented the Consualia festival, as a way of gathering his Sabine neighbors at a celebration that included horse-races and drinking. During these distractions, Romulus's men then abducted the Sabine daughters as brides. Thus the famous Roman myth of the Rape of the Sabine women had as its setting the Circus and the Consualia.

In this quasi-legendary era, horse or chariot races would have been held at the Circus site. The track width may have been determined by the distance between Murcia's and Consus' shrines at the southeastern end, and its length by the distance between these two shrines and Hercules' Ara Maxima, supposedly older than Rome itself and sited behind the Circus' starting place.

In later developments, the altar of Consus, as one of the Circus's patron deities, was incorporated into the fabric of the south-eastern turning post. When Murcia's stream was partly built over, to form a dividing barrier (the spina or euripus) between the turning posts, her shrine was either retained or rebuilt. In the Late Imperial period, both the southeastern turn and the circus itself were sometimes known as Vallis Murcia.

Temples to several other deities overlooked the Circus; most are now lost. The temples to Ceres and Flora stood close together on the Aventine, more or less opposite the Circus' starting gate, which remained under Hercules' protection. Further southeast along the Aventine was a temple to Luna, the moon goddess. Aventine temples to Venus Obsequens, Mercury and Dis (or perhaps Summanus) stood on the slopes above the southeast turn. On the Palatine hill, opposite to Ceres's temple, stood the temple to Magna Mater and, more or less opposite Luna's temple, one to the sun-god Apollo.

Sun and Moon cults were probably represented at the Circus from its earliest phases. Their importance grew with the introduction of Roman cult to Apollo, and the development of Stoic and solar monism as a theological basis for the Roman Imperial cult. In the Imperial era, the Sun-god was divine patron of the Circus and its games. His sacred obelisk towered over the arena, set in the central barrier, close to his temple and the finishing line.

The Sun-god was the ultimate, victorious charioteer, driving his four-horse chariot (quadriga) through the heavenly circuit from sunrise to sunset. His partner Luna drove her two-horse chariot (biga); together, they represented the predictable, orderly movement of the cosmos and the circuit of time, which found analogy in the Circus track.

The Sun-god was the ultimate, victorious charioteer, driving his four-horse chariot (quadriga) through the heavenly circuit from sunrise to sunset. His partner Luna drove her two-horse chariot (biga); together, they represented the predictable, orderly movement of the cosmos and the circuit of time, which found analogy in the Circus track. In Imperial cosmology, the emperor was Sol-Apollo's earthly equivalent, and Luna may have been linked to the empress. Luna's temple, built long before Apollo's, burned down in the Great Fire of 64 AD and was probably not replaced. Her cult was closely identified with that of Diana, who seems to have been represented in the processions that started Circus games, and with Sol Indiges, usually identified as her brother. After the loss of her temple, her cult may have been transferred to Sol's temple on the dividing barrier, or one beside it; both would have been open to the sky.

Several festivals, some of uncertain foundation and date, were held at the Circus in historical times. The Consualia, with its semi-mythical establishment by Romulus, and the Cerealia, the major festival of Ceres, were probably older than the earliest historically attested "Roman Games" (Ludi Romani) held at the Circus in honor of Jupiter in 366 BC.

In the early Imperial era, Ovid describes the opening of Cerealia (mid to late April) with a horse race at the Circus, followed by the nighttime release of foxes into the stadium, their tails ablaze with lighted torches. Some early connection is likely between Ceres as goddess of grain crops and Consus as a god of grain storage and patron of the Circus.

The most important event at the Circus was chariot racing. The track could hold 12 chariots, and the two sides of the track were separated by a raised median termed the spina.

The most important event at the Circus was chariot racing. The track could hold 12 chariots, and the two sides of the track were separated by a raised median termed the spina. Statues of various gods were set up on the spina, and Augustus erected an Egyptian obelisk on it as well. At either end of the spina was a turning post, the meta, around which chariots made dangerous turns at speed. One end of the track extended further back than the other, to allow the chariots to line up to begin the race. Here there were starting gates, or carceres, which staggered the chariots so that each travelled the same distance to the first turn.

Very little now remains of the Circus, except for the now grass-covered racing track and the spina - the outline of the central barrier. Some of the starting gates remain, but most of the seating has disappeared. After the 6th century, the site fell into disuse and gradual decay. Some of its stone was recycled, but many standing structures survived for a time.

In 1587, two obelisks were removed by Pope Sixtus V, and one of these was re-sited at the Piazza del Popolo. The lower levels of site, ever prone to flooding, were gradually buried under waterlogged alluvial soil and accumulated debris; the original level of track is now buried 6m beneath the modern surface.

In the 12th century, a watercourse was dug to drain the soil and by the 1500s the area was used as a market garden.

Mid 19th century workings uncovered the lower parts of a tier and outer portico. Since then, a series of excavations has exposed further sections of seating, curved turn and central barrier but further exploration has been limited by the scale, depth and waterlogging of the site.

The Circus still occasionally entertains the Romans; being a large park area in the centre of the city, it is often used for concerts and meetings. The Rome concert of Live 8 (July 2, 2005) was held there, as was the Italian World Cup 2006 victory celebration.

The Obelisco Flaminio in Piazza del Popolo.

The Obelisco Flaminio in Piazza del Popolo.This obelisk was removed in the 16th century by Pope Sixtus V and placed in the Piazza del Popolo. Excavation of the site began in the 19th century, followed by a partial restoration, but there are yet to be any truly comprehensive excavations conducted within its grounds.

The Circus Maximus retained the honor of being the first and largest circus in Rome, but it was not the only example: other Roman circuses included the Circus Flaminius (in which the Ludi Plebeii were held) and the Circus of Maxentius. The Circus is still occasionally used as an entertainment area. The Rome concert of Live 8 in July 2, 2005 was celebrated there.

Hippodrome

A Hippodrome (Gr. from hippos, horse, and dromos, race, course) was a course provided by the Greeks for horse racing and chariot racing. Some present-day horse racing tracks are also called hippodromes, for example the Central Moscow Hippodrome. The Greek hippodrome corresponded to the Roman Circus Maximus, except that in the latter only four chariots ran at a time, whereas ten or more contended in the Greek games, so that the width was far greater, being about 400 ft., the course being 600 to 700 ft. long. The hippodrome should not be confused with the Roman amphitheatre which was used for spectator sports, games and displays, or the Greek and Roman theatres which were semi-circular and used for theatrical performances.

The Greek hippodrome was usually set out on the slope of a hill, and the ground taken from one side served to form the embankment on the other side. One end of the hippodrome was semicircular, and the other end square with an extensive portico, in front of which, at a lower level, were the stalls for the horses and chariots. At both ends of the hippodrome there were posts (termai) that the chariots turned around. This was the most dangerous part of the track, and the Greeks put an altar to Taraxippus (disturber of horses) there to show the spot where many chariots wrecked.

A large ancient hippodrome was the Hippodrome of Constantinople, built between AD 203 and 330. However, since it was built to a Roman design, it was actually a circus.